(2025) I had been farming for about ten years when the “farm crisis” of the 1980s reached one of my neighbors. His son came home for Christmas from the university, to be told that the family could no longer afford to keep him in college. The son committed suicide.

I was sad and wanted to be useful. With a few other people, I found partners in a rural Catholic parish, elders in a United Church of Christ in two different counties, and Baptist leaders among black farmers in yet a different county. I sought out and learned from successful rural community organizers. I promoted resolutions for my local Farm Bureau board. We had a “farm crisis hotline” that we answered from our kitchen phone. I found allies in other states, and we started to work on policies.

After several months, I got occasional calls from a man I had come to revere; John Berry was a senior statesman among farmers. He thought that I should learn from him, and he was right. He would come on the line with his raspy voice: “Hal, I want you to come talk with me, young man.” He didn’t want me to talk at all. He wanted to tell me his story.

Mr. Berry’s story began when he was a little boy in 1906, waiting with his mother and brother for his father to return from selling the year’s crop at the tobacco warehouse. Money was very tight, and his mother was anxious. His father eventually rode up, stabled his horse, and told the family that their year’s work earned less than the cost of the sales commission.

As a young man in the 1920s, Mr. Berry volunteered to sign up other farmers to the nascent Burley Tobacco Growers Cooperative. Their goal was to bargain with the companies. Mr. Berry told me that everyone got enthusiastic and hoped for success, but “when it was time to come up and sign the membership roll, there weren’t enough doors in the schoolhouse for everyone trying to leave.” He persevered though.

When an aspiring candidate for Congress came through town and gave an electioneering speech, Mr. Berry’s neighbors turned to him and said, “Johnny, you’ve been to the university, and you want to solve the farm problem. You get up there and give a speech too.”

Later, after the election, the newly elected congressman talked John Berry into coming to Washington with him to be his aide. They helped write New Deal farm legislation that resulted in the Upper South sustaining more small farms than anywhere else in the country. Mr. Berry concluded that only government had the power to enforce fairness in an unequal market, and that a program needed to be mandatory. “Otherwise, the biggest farmers will always go around the rest of us and make their own deals.”

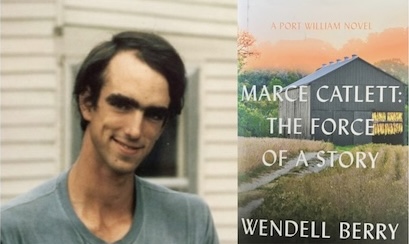

Wendell Berry, John’s oldest son, recently published his father’s story: Marce Catlett: The Force of a Story. This was the story that Mr. Berry had told me several times. Wendell writes of his father, and then of himself [with his fictionalized name Andy]: “Because of the story, there were … certain things that he had to do. Andy and his children have been similarly limited and prompted by this story, [which is] revealed to its followers only by love for those they follow, for one another, and by the daylight as it comes.”

Because Mr. Berry chose me to mentor, his story became part of my story too, evolving through the years as I worked with farmers and food companies and everyone else in the complex system we call “agriculture.” We’ve had to evolve the story in the wake of recurring challenges. New Deal programs succumbed to global markets. Tobacco was diagnosed as a deadly drug. And Henry County Kentucky is a ghost of the community that used to be. But we still work for “the daylight as it comes,” believing in our hearts that the land and its people are endlessly redeemable.

Mr. Berry’s story lives alongside a story that blossomed in the 1950s with aspirations for free market efficiency but proceeded to grow not only productivity but also ecological and social damage. A new story for the 21st century blends New Deal aspirations for the common good with restoration of the countryside.

The current evolution of “regenerative agriculture,” rooted in practices that restore the biological health of soil, is spreading past a few innovators to their mainstream neighbors. This evolution into a new phase of agriculture requires local learning and trusted advisors. If complemented by markets and policies that reduce financial pressures, rural communities have the potential to bridge “red” and “blue” cultures as farmers launch a second “green revolution.”